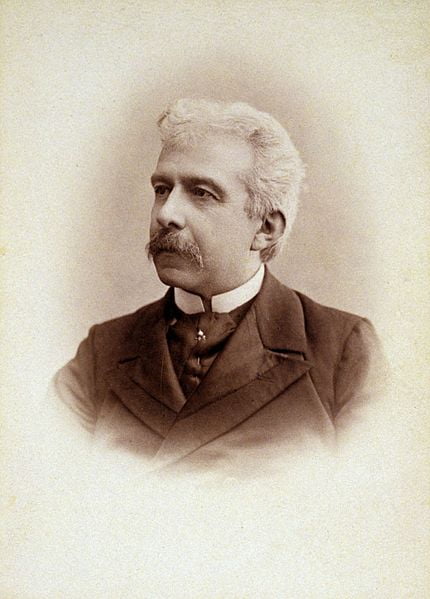

Antonio Fogazzaro (1842-1911)

Born at Vicenza in northern Italy, Fogazzaro led a very active life, both as senator and writer. Though he studied at first for the law, he was soon able to devote himself largely to writing. His novels (and in particular The Saint) brought him international fame. During his most prolific period he wrote a few volumes of exquisite short stories, among which one of the best is The Peasant`s Will. It is wholly representative of this writer`s art, serene, sympathetic, natural.

The present version is translated by Walter Brooks, and is reprinted from his volume, Retold in English. Copyright, 1905, by Brentano s, by whose permission it is here included.

The Peasant`s Will

In my earlier days I was the assistant of Lawyer X, of Vincenza, when one day in August, about ten o`clock in the morning, a young peasant of Rettorgole came into the office and begged the lawyer to go with him to his home for the purpose of drawing up the will of his father who was, as he expressed it, “mal da morte.”

My principal assented, and, wishing me to accompany him, we all three started off, squeezed into a rickety country cart without springs and drawn by a sorry nag of uneven gait. The seat which we occupied was cushionless and hardly added to the comfort of two not over-stout

individuals, each accustomed to his own easy-chair. X`s face wore an expression of agony, and he cried oui at every jolt. I suffered in silence, and the peasant imperturbably described the illness of his father, a certain Matteo Cucco, nicknamed “L`orbo da Rettorgole,” because he had only one eye. “But he can see more with that one than most people could with three,” remarked the afflicted and respectful son.

We were hardly outside the city when we left the main road and turned into a narrow and muddy lane running through a succession of low-lying meadows, where the cart jolted even more than ever, but fortunately we were not long in arriving at our destination. We found there a miserable tumble-down house planted in the midst of mud and mire. A stable, open below and with a hay-loft above, was built against one end of it, and combined to provide shelter under the same roof for man and beast.

X and I were about to enter the kitchen when our conductor informed us that the sick man was not in the house. The heat and filth of his room had become such as to make it necessary to remove him to the hay-loft. Entrance to this was to be had only by climbing a ladder made of a single pole with pegs driven through it at intervals to serve as primitive rungs.

Read More about The Shipwreck of Simonides