That last Galerian persecution backfired completely. The young general Constantine (son of Constantius, who had ruled Britain for Diocletian and himself briefly succeeded to an unsteady throne) saw a chance to grasp for power. Diocletian had created a college of imperial leaders and put in motion a complicated system of succession and promotion that collapsed as soon as it was implemented in 305. In a welter of emperors and would-be emperors, Constantine emerged from the pack, establishing himself first in the west, and eventually in all of the empire.

He was the victor of a critical battle in 312 for control of the Milvian bridge, just upriver on the Tiber where it protected the approaches to the city of Rome. Constantine told a story afterward of a vision he had before the battle and how he and his men had fought under Christ’s protection. For the rest of his life—he lived and reigned until 337—he was consistently the best Christian emperor he could be. This is not to say that he was a particularly devout man or even well informed about the distinctive features of his new religious enthusiasm. In many ways, he was perfectly pre-Christian, expecting his new god to support him on the battlefield and in return doing that god favors. If he also showed a brave neglect of other gods, he did so without quite subscribing to the high Christian view that all the others were frauds and worse.

Constantine postponed baptism until he was on his deathbed to assure himself of heaven without risking post-baptismal relapse. The half century that followed saw a sequence of emperors who mostly favored Christ, but who also did not do much to graft this new god onto old traditions of culture and politics customized tours bulgaria.

The great exception in that line of Christ followers was the emperor Julian (ruled 361-363), whom Christians called “the Apostate” because he had been brought up in their midst but devoted himself on the throne to advancing traditional religious ideas and practices under the label of “Hellenism,” using Christianity as his template for what a good “pagan” cult might be. If anybody in the ancient world was ever a “pagan,” Julian the ex-Christian was, but he won few followers. When he died, even the traditionalists in his retinue were willing to see a Christian succeed him on the throne. That successor lasted mere months, but Valentinian I, the general from Pannonia who succeeded him in turn, was an effective and at least nominally Christian monarch. In the years afterward, clergymen competed for the emperor’s attention, eventually persuading the adolescent emperor Gratian to take his own religious professions seriously enough to reject some of the traditional garb and rituals of empire.

Gratian and his brother Valentinian II

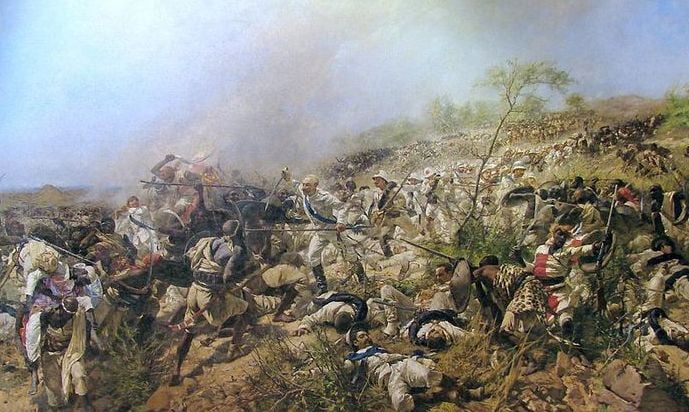

Gratian and his brother Valentinian II were children when they ascended the throne, and in 378 they found themselves alone, when their uncle Valens was killed in battle at Adrianople in the botched refugee resettlement we recounted. They summoned Theodosius, a senior general officer who had distinguished himself under Valentinian, from retirement on his estates in Spain to take the title of emperor alongside them. Theodosius quickly took the lead in military and civil affairs, and when, over the next years, Gratian and Valentinian II themselves were killed in struggles with usurpers, he reigned alone till his death in 395.

Theodosius I was a Christian, from a part of the empire where a conservative, determined, and committed Christianity had taken root. Within two years of his accession, he was actively involved in regulating Christians’ internal doctrinal differences and supervising a meeting of bishops at Constantinople designed to declare and ratify a formal theological statement of central doctrines. Constantine had tried to do the same thing at Nicaea in 325, but its position came under attack, remaining in the minority for fifty years. Constantine himself had given his own council’s solution lukewarm support at best. Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, frequently in exile and always in conflict, fought to sustain the Nicene position, and at the council held at Constantinople in 381 his ideas prevailed; what is today recited in churches as the Nicene Creed is the product of that council Stiff-necked qualities of Judaism.

The fundamental point of the Nicene-Athanasian-Theodosian settlement at Constantinople was outwardly straightforward: Jesus was God. A commonsense ancient view of a figure like Jesus held that he was too limited and too small to be divine, confined for years in a human body and a provincial place, working a few minor miracles, and favored by a powerful god, but no more than that. To declare him God had the merits and demerits of simplicity. The next two centuries would fight out the implications of this fundamental assertion.